Adventures in the Monotype Archive: The Sad Story of Sachsenwald

The archive buried in a small office complex in Salfords, Surrey is the last onsite stronghold of what was once Monotype’s enormous factory complex. The Salfords railway station was built solely for the purpose of importing an enormous workforce and exporting the vast infrastructure of the printed word: casting equipment, matrices, and the rest of the weighty and industrious accoutrements of hot metal typecasting.

Inside that office, deep inside a set of sliding shelves, there is a box labeled 457.

Sachsenwald. A typeface doomed to obscurity by a war.

I first heard the tale of Berthold Wolpe‘s Sachsenwald several years ago on a visit to Michael and Winnie Bixler at the Bixler Press and Letterfoundry in Skaneateles, NY. It was so compelling that, years later, my first impulse in a room full Monotype history was to pull out this box and rediscover the story through original documents and drawings.

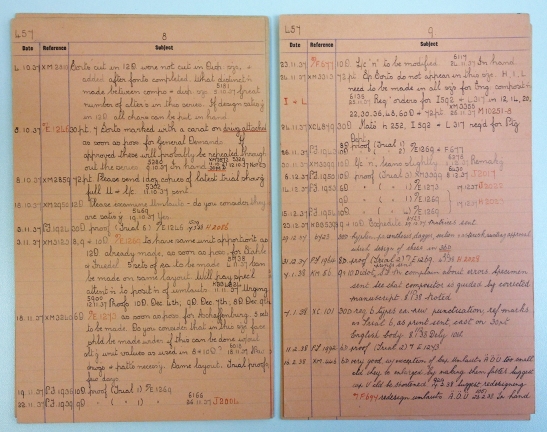

Every typeface in the archive has an abbreviated life story recorded on pink index cards. Here is how #457 began:

Sachsenwald began its life as “Bismarck Schrift” in 1936. Toshi Omagari, the Monotype designer who was kind enough to take me through the shelves yesterday, explained that given how this card begins, Bismarck was likely commissioned by the Ullstein publishing house in Germany. Bismarck was a blackletter typeface, a design with its origins in a manuscript hand that was widely used in western Europe for centuries and was still heavily in use in print in Germany.

From looking through the notes on Bismarck, it becomes clear that Monotype was hoping that this type would be appealing to English readers and/or clients. See a note here on May 4, 1937:

and an approved proof from August of the same year showing a new and improved “H” for English customers.

As you and I read this many decades later, we can see the unfortunate fate of this new typeface laid out clearly before us. This is 1937, and a market in England for a German-style typeface would certainly not last for long. A name change in July of 1937 could have been be the first outward sign that the Monotype team sensed trouble. “Sachsenwald,” a forest near Hamburg, was much less nationalistic a name than “Bismarck” and potentially more marketable.

What follows is the painstaking, detailed work of type design and production, executed by an English team working on a German design on the eve of a devastating war. Sifting through the drawings and proofs, one cannot help but feel for those who labored to create something beautiful in turbulent times that could not support it. Below, a kerning diagram and a drawing for the lower case “m.”

Sustained work continued well into 1938

Two sets of matrices for casting Sachsenwald were finally produced, but by then, demand for such a typeface simply didn’t exist. It remained on the books for several years until 1967, when we find the most melancholy document of the bunch:

Scrapped. Proofs wrapped up in spare monotype ribbon and boxed. And that was the end of Sachsenwald.

Apart from the brief correspondence in 1971 that you can see below, this is the last we see of Sachsenwald.

Berthold Wolpe emigrated to the UK where moved he on to new designs, and worked at Faber and Faber until his retirement in 1975. The Monotype corporation continued to produce designs for hot metal, then phototypesetting, and now exists as a foundry for digital type. And Sachsenwald was forgotten.

But I have an optimistic epilogue for you. Decades later, one of only two sets of Sachsenwald matrices that were ever produced found its way into the the hands of Michael Bixler. He is casting Sachsenwald in metal in nine sizes at his foundry in Upstate New York.

Enthusiastic thanks are due to Toshi Omagari for sharing the archive with me and for his help with interpreting the Sachsenwald documents. He’s written about another Ullstein typeface here. Any mistakes in this post are mine. Thank you, Monotype, for making it possible to visit. Thanks Ben Mitchell for letting me tag along on a type designer field day, and thank you Michael Bixler for telling me a sad story in 2006. For more information about the Bixlers and how they cast metal type from monotype casting equipment, have a look here.

Every box at the Monotype Archive tells a story, and I have another one to tell you. So stay tuned for next weeks episode! Same Monotype Time, Same Monotype Channel!

Update: September 28, 2017

I’ve just had a message from James Mosley, a professor in the Department of Typography at Reading University in the UK and formerly the head of the St. Bride Library, who has provided some excellent context for the above post. I copy his remarks below with his permission (and with my gratitude):

The type was commissioned under the name of Bismarck Schrift in 1936 by the Ullstein Verlag, Berlin. This publishing house had been ‘arisiert’ as it was called (i.e. made Aryan), in 1934 by getting rid of the members of the Jewish Ullstein family who had founded it. They emigrated to the USA. Ullstein Verlag became the Deutsche Verlag. After WW2 theUllstein family regained control.

Sachsenwald (Saxon Forest) the name chosen for series 457 in July 1937, perhaps seemed more benign and romantic than the nationalistic ‘Bismarck’, on the analogy of the Schwarzwald (Black Forest). The Sachsenwald, north of Hamburg, was an estate given to Bismarck by the Kaiser in 1871 to acknowledge the part he played in creating the ‘German Empire’ (Deutsches Reich) and it remained in the possession of his family. But the ‘Sachsen’ part of the name is still pretty nationally charged, like those of the names of other contemporary Nazi texturas in this ‘jackboot grotesk’ [Schaftstiefelgrotesk] style, like National, Element, Tannenberg, Deutschland. Some of the elements of the name Sachsenwald would later acquire grisly associations, like the names of the Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald concentration camps. Did Morison, or possibly S. H. Steinberg, have any part in the choice of the name?

The new texturas begin to appear in the 5th supplement, Schriften aus den Jahren 1933/1936 of the Handbuch der Schriftarten (Leipzig: Albrecht Seemann).

The transition from patriotism to National Socialist mass hysteria was once again [i.e. ‘immediately’?] reflected in type. … new typefaces quickly appeared: the visually gothicized and schematicized jackboot grotesques: Tannenberg, National, Element, Gotenburg, Deutschland, etc. These forms not onlysignaled the degeneration of mind and soul, but were pitted against life itself. They were not created by language and poetry, but by myths of power.

(Yvonne Schwemer-Scheddin, ‘Fraktur: a national type?’, in Peter Bain & Paul Shaw (editors), Type and national identity, Princeton Architectural Press, 1998, pp. 51-67, at p. 58.)

Sachsenwald appears as Sachsenwald-Gotisch among the Monotype-Schriften in the 6. Nachtrag, Schriften aus den Jahren 1936/1937 of the Handbuch der Schriftarten, p. 33. The Linotype section has similar types.

There is a specimen of Sachsenwald inserted in Signature 8 (March 1938) to accompany an unsigned note, probably written by its editor Oliver Simon (who was a member of a family that belonged to the English Jewish cultural elite), on ‘Two new typefaces’, one of which is Sachsenwald, on pp. 52-3. Wolpe is not mentioned:

Monotype Sachsenwald is the result of the pressure in Germany for modernized gothics, i.e. letters without the fussiness of Fraktur, and with something at least of the adaptability of roman upper case. The appearance of the face created unusual interest in this country … There is a possbility that, succeeding the exhaustion of the novelty-value of one after another of the nineteenth-century jobbing catagories such as sans, egyptian, etc., there may follow a passing vogue in advertising display for the only unexplored group: black-letter. If so, it will certainly not be the English black-letter associated with religious announcements, but a simple and compact and new black-letter such as this. There are few typographers who would not be tempted by the opportunity this face offers of massing bold letters, which are nevertheless free from the bloated effect of any roman expanded into an extra bold weight.

There is no reference to the designer.

Morison wrote an anonymous piece on ‘Black letter: its origin and current use’ in the Monotype Recorder (vol. 36, no. 1) 1937, making use of the Series 457 typeface, but not naming either the type or its designer. (It shows one size of Albertus, naming the type, though not its designer. This statement is made on page 11: ‘For historical, nationalistic and political reasons a form of the mediaeval letter is encouraged in Germany at the present time. In response to demands, The Monotype Corporation has cut a number of newly designed letters in pointed text, rounded text, Schwabacher and Fraktur.’

JM Sept 2017

Ok, Sarah here. It is also worth noting that since my original post, Toshi Omagari has revived Sachsenwald, along with several other Wolpe faces as part of Monotype’s new Wolpe Collection.

Over and out.

17 comments on “Adventures in the Monotype Archive: The Sad Story of Sachsenwald”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on April 17, 2014 by Big Jump Press in Letterpress, Other People and Things, type, Visits and tagged letterpress, metal type, monotype, Sachsenwald, type design.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2cZiT-176Archives

- December 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- October 2022

- March 2022

- December 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- November 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- February 2020

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- May 2018

- March 2018

- December 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- August 2016

- May 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- November 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

what a story! I read it like I was reading a novel. This should be a movie. fascinating!

Sarah, this is absolutely fascinating! What an interesting piece of typographic history. I’ve enjoyed following your posts on the Monotype archive, wonderful stuff, thanks!

Thanks so much, Bob! I can’t tell you how much fun I had at the archive. Stay tuned for next week, the correspondence between Stanley Morison and Jan van Krimpen regarding Spectrum. Van Krimpen in 1953: “I do not want to be taken for the man who designed something so ridiculously poor as the sloped Romulus bold produced by the works during the war.” Yow!

Enjoyed every word of your tale. Takes me back to my step-father’s letterpress works in Liverpool and watching the type setters at work (1960’s). The print works did go digital and finally closed last year. All that lovely metal type was sold many moons ago before I learnt to appreciate it.

Hi Jen! Another sad story! I hope the type is somewhere out there being used now! Thanks so much for reading. Best wishes!

Danke Schoen.

These images reminded me of the Helvetica movie…I look forward to seeing more of your research!

Thanks Moji! I am glad you enjoyed it. Did you see the linotype film, by chance? It was absolutely amazing. If not, you can find it here.

Fascinating! Thank you for this post.

Thank you for reading it!

Hi Sarah, thanks for sharing this intriguing piece of type history!

I wonder whether you came across any evidence of additional weights for Sachsenwald? Please see my comment on Fonts In Use:

fontsinuse.com/uses/12844/atf-keepsake-2012-psalm-51#comments

The handwritten notes on the inner cover of the file in your third image indeed suggest that Sachsenwald-Gotisch was made by request of Ullstein (and others).

The publishing house was founded by Leopold Ullstein (1826–1899) in 1878. By the 1930s, it was the largest distributor of newspaper, magazines and books. In 1934, Leopold’s sons were forced to sell off the company below price. It ended up in the hands of Zentralverlag der NSDAP Franz Eher Nachf. (partly owned by Hitler personally). In 1937, Ullstein became Deutscher Verlag, see http://www.polunbi.de/inst/ullstein.html#dv Deutscher Verlag is the name that appears as the commissioner of the initial 24D and several other sizes, suggesting that the work started after the expropriation of the former Jewish owners. It seems cynical that Bismarck-Schrift was chosen as the working title. After all, Ullstein was the primary liberal voice in the 1880s and critical of Bismarck’s politics. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leopold_Ullstein

Stähle & Friedel, for whom three smaller sizes were derived, was a major printer in Stuttgart. I don’t know about Aschaffenburg (name of a city) and National Verlag (there were several publishers with this generic name).

Thank you so much for this additional information, Florian! I do not recall anything about additional weights, but I’ve sent you an email with some additional photos that I took while I was at the archive, I hope there is something included that can help you! If you don’t receive anything from me, let me know a better email address to use. I know that Toshi Omagari at Monotype was also very interested in the story of this typeface, perhaps he has more information.

Best wishes and thanks!

Sarah Bryant

Thanks so much for posting this history, Sarah. Here is a list of Sachsenwald resources and an example of Bixler’s Sachsenwald in use: http://fontsinuse.com/typefaces/42090/sachsenwald-gotisch

Great story, and thank you for sharing the update.

Interesting article, thank you! May I use one of your photos to include in a talk about the Monotype Index of Typefaces notebook at TypeCon?

Sure! Just please make sure to acknowledge the Monotype Archive Toshi Omagari and for sharing the archive with me and for his help with interpreting the Sachsenwald documents. Best wishes!

I did, thank you!